This year marks the centenary of the publication of Ananda Coomaraswamy’s scholarly and exquisite Medieval Sinhalese Art By Ismeth Raheem In December 1908, Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy penned the following words in the introduction to his book, “Medieval Sinhalese Art”:

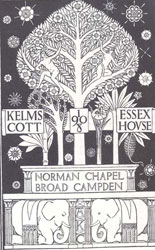

“It is of interest to record, in connection with the arts and crafts aspects of the questions just discussed, that this book has been printed by hand, upon the press used by William Morris for printing the Kelmscott Chaucer. The printing carried on in the Norman Chapel at Broad Campden has occupied some fifteen months. One cannot help seeing in these very facts an illustration of the way in which the East and the West may together be united in an endeavour to restore that true Art of Living which has long been neglected by humanity. Four-hundred-and-twenty-five copies printed under the care of the Author at the Essex House Press in the Norman Chapel at Broad Campden, Gloucestershire. Begun in September, 1907 and finished in December, 1908.”This year marks the centenary of the publication of “Medieval Sinhalese Art” –probably the most celebrated hand-printed book on Sri Lanka.

The print mark design by C.R. Asby first used in Medieval Sinhalese Art Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy (1877-1947) is known the world over as one of the great scholars of Indian art. The bulk of his writings on art and philosophy was published during the 30 years (1917 to 1947) he was curator of the Indian section of the Museum of Fine Arts, in Boston, in the US.

When Ananda and Ethel Coomaraswamy (1872-1952) began researching material for “Medieval Sinhalese Art” in 1903 (the book would be published in 1908), they were barely conscious of the pioneering work that lay ahead. They were putting into practice a theoretical model for a work that would redefine the study of Sri Lankan arts and crafts.

Although, over the past century, “Medieval Sinhalese Art” has achieved canonical status among scholars and artists around the world, Coomaraswamy’s message, as set out in his book, has never been taken very seriously by today’s generation of Sri Lankans, particularly the artists, architects and designers.

On March 7, 1903, Ananda and Ethel Coomaraswamy, who were 25 and 29 years old respectively, sailed to Colombo to begin an uninterrupted period of research that would continue till December 1906. During this period Coomarswamy was also director of the Mineralogical Survey, the first person to hold this post.

Coomaraswamy’s life was full of ambiguities. He was formed by a host of influences whose variety is reflected in his very name – Ananda (Indian) Kentish (English) Coomaraswamy (Tamil-Sri Lankan). He was a natural scientist. He was trained in England as a geologist, and he founded the Geological Survey of Ceylon, of which he was the first director. As a pioneering art historian and scholar, the three books he wrote on art, including “Medieval Sinhalese Art”, have achieved the status of classics.

Coomaraswamy was schooled in England. He obtained a first-class degree in geology and botany from the University of London in 1901. In 1906 he was awarded a doctorate for his work in Ceylon conducted between 1902 and 1906. The results of his efforts persuaded the British administration to set up a department for geological surveys. It was exhaustive field work, carried out in remote areas,-but the happy outcome was Coomarswamy’s discovery of the mineral “thorianite”. He discussed thorianite’s radioactive properties in his correspondence with the scientist Marie Curie (winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1903, and the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1911).

While exploring the country, he became impressed with the vanishing life and culture of the people. Thus began his fierce, lifelong indignation at the dismissive British attitude towards Sri Lankan art and culture.

When Ananda and Ethel Coomaraswamy (1872-1952) began researching material for “Medieval Sinhalese Art” in 1903 (the book would be published in 1908), they were barely conscious of the pioneering work that lay ahead. They were putting into practice a theoretical model for a work that would redefine the study of Sri Lankan arts and crafts.

Although, over the past century, “Medieval Sinhalese Art” has achieved canonical status among scholars and artists around the world, Coomaraswamy’s message, as set out in his book, has never been taken very seriously by today’s generation of Sri Lankans, particularly the artists, architects and designers.

On March 7, 1903, Ananda and Ethel Coomaraswamy, who were 25 and 29 years old respectively, sailed to Colombo to begin an uninterrupted period of research that would continue till December 1906. During this period Coomarswamy was also director of the Mineralogical Survey, the first person to hold this post.

Coomaraswamy’s life was full of ambiguities. He was formed by a host of influences whose variety is reflected in his very name – Ananda (Indian) Kentish (English) Coomaraswamy (Tamil-Sri Lankan). He was a natural scientist. He was trained in England as a geologist, and he founded the Geological Survey of Ceylon, of which he was the first director. As a pioneering art historian and scholar, the three books he wrote on art, including “Medieval Sinhalese Art”, have achieved the status of classics.

Coomaraswamy was schooled in England. He obtained a first-class degree in geology and botany from the University of London in 1901. In 1906 he was awarded a doctorate for his work in Ceylon conducted between 1902 and 1906. The results of his efforts persuaded the British administration to set up a department for geological surveys. It was exhaustive field work, carried out in remote areas,-but the happy outcome was Coomarswamy’s discovery of the mineral “thorianite”. He discussed thorianite’s radioactive properties in his correspondence with the scientist Marie Curie (winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1903, and the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1911).

While exploring the country, he became impressed with the vanishing life and culture of the people. Thus began his fierce, lifelong indignation at the dismissive British attitude towards Sri Lankan art and culture.

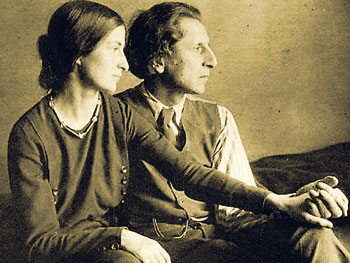

Coomaraswamy married his first wife, the Englishwoman Ethel (nee Partridge) in 1902. Ethel, five years Coomaraswamy’s senior, was an accomplished artist, photographer, scientist and linguist. Towards the end of her stay in Sri Lanka, she undertook the task of translating the historical epic, the Mahavamsa, from German to English.

Coomaraswamy with Ethel Most of the plates in “Medieval Sinhalese Art” are photographic images taken by Ethel Coomaraswamy. During the Coomaraswamy’s stay in Sri Lanka, Ethel captured more than a thousand images on glass plate negatives.

When the couple returned to England, Ananda Coomaraswamy bought shares in the Guild of Handicrafts in 1907 and took over the Essex House Press. This enabled him to embark on his distinguished career as an art historian by becoming his own publisher, printing a special edition of “Medieval Sinhalese Art” in a limited edition of 425 copies. This also gave him a creative role in the Arts and Crafts Movement, which he came to admire after reading the writings of William Morris.

He saw to it that the printing of his encyclopedic work on the minor arts of Ceylon was carried out with imaginative design, using craft traditions and high-quality materials. The medium was perfectly suited to the subject.

Inherited wealth enabled Coomaraswamy to settle in a beautiful re-styled manor house in the Cotswolds. The Arts and Crafts Movement was named after the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, founded in England in 1882. One aim of the Arts and Crafts Movement was to recreate the vernacular tradition, which was being submerged by the Industrial Revolution. The movement spread from England to Europe and then to America, and later to countries like India and Sri Lanka.

The activities and publications of the Arts and Crafts Movement played a dominant role in the Coomaraswamys’ last years.

1 Comment

Hi,

Interesting Blog……..

Providing a brief knowledge about Basel II.basel ii training