Ever since Andy Warhol, the worlds of art and finance have been inseparable. On the eve of Tate Modern’s Pop Life exhibition, Sean O’Hagan visits five art superstars in their studios to find out how the market drives their creative process

Damien Hirst in his studio in Stroud, Gloucestershire. Photograph: Karen Robinson

Next month, Tate Modern will host a stellar group show entitled Pop Life. Apparently, the show was going to be called Sold Out – a much more provocative and, some would say, apposite title, given that among the themes addressed by the curators is the notion of the artist as brand. Think Damien Hirst, think Jeff Koons, think, above all, Andy Warhol.

Twenty-two years after his death, and over 40 years after his ascendancy as America’s most famous Pop artist, Warhol remains an influential figure on the making and selling of art. As his most obvious heir, Damien Hirst, puts it, “Warhol really brought money into the equation. He made it acceptable for artists to think about money. In the world we live in today, money is a big issue. It’s as big as love, maybe even bigger.”

In a culture in thrall to advertising, marketing and celebrity, Warhol made art that mirrored that hyper-real world of commodification even as it critiqued it. His definition of the word artist was “someone who produces things that people don’t need to have”. He called his studio the Factory and his means of production defined the ultra-capitalist creed by which many successful younger artists now live. “Being good in business is the most fascinating kind of art,” he wrote.

To see how art and money co-exist at the highest level, you need to attend an international art fair, or better still, a Sotheby’s auction. If you want to dig deeper, though, to find out how much the creative process has altered to accommodate the market, the artist’s studio is still the best place to visit.

Hirst’s main studio is in Stroud in rural Gloucestershire. It comprises a huge hangar-like room and various smaller offices situated opposite an old house he is currently renovating. The floors of the house are paved with ornately inscribed Victorian gravestones, the walls panelled in dark wood decorated by carved skulls and skeletons. Hirst has absorbed Warhol’s obsession with death as well as his acute business acumen. He is now the world’s most expensive living artist, his diamond-encrusted human skull, For the Love of God, a kind of memento mori for the days of art-market hysteria that preceded the current global recession.

Like the two main contenders for his throne, Jeff Koons and Takashi Murakami, Hirst is essentially an ideas man. The ideas he hatches in his head are converted into artworks by a team of assistants that, until recently, numbered 150. The day I visited, though, his vast studio space in Stroud seemed eerily empty, save for a gaggle of multi-coloured skeletons that stood sentinel at one end. A single glass case on a plinth housed a life-sized human skull made out of hundreds of dead house flies. Possibly a metaphor for the art market.

In stark contrast, Jeff Koons’s studio complex in midtown Manhattan was a hive of activity. In the main office, Koons sat at a computer working on ideas, prototypes, drawings, while an assistant showed me around the web of interlinked rooms. In one long, well-lit space, eight huge paintings were being worked on simultaneously by groups of two or three artists. In another, a team of masked and white-suited assistants laboured over a giant inflatable lobster. It looked like some weird sci-fi operating theatre. Despite Koons’s air of unreal calmness, it was an oddly unrelaxing place to be.

The next day, I travelled out to Long Island to Takashi Murakami’s studio. In one room, a single “superflat” painting lay on a table. The latest layer of paint, laboriously applied by several assistants to his precise specifications, was slowly drying. Nearby stood an assortment of Perspex boxes, numbered and coded, containing paint pigments. An assistant insisted that they had catalogued around 40 shades of white. “Murakami is a little obsessive,” she said, smiling. That much was evident.

In another room, we watched one of his animated short films, a futuristic whimsy that involved a Godzilla-like monster and a giant animated turd. “Murakami is obsessed with poo-poo,” the same assistant explained. I wondered if this infantile world of cuddly soft toys and ejaculating super-heroes reflected our own increasingly infantile culture, or was simply another aspect of it.

It was something of a relief, then, to visit Gavin Turk’s studio in a lock-up in Hackney, east London. He was hanging a huge screen print on the wall as I came in. It was a Warhol-style self-portrait. This was doubly – or perhaps triply – ironic because his workspace was the least Factory-like of all those I visited and seemed the least driven by the art market. It appeared instead like a place where an artist actually worked hands-on, making his art.

“It’s a workshop,” Turk said, matter-of-factly. “A place where you can just go and make stuff.” It looked messy and disordered and somehow real. It smelled of paint, dust, chemicals and cooking. It did not smell of money. It seemed almost quaint, but this is how most artists still live. The art superstars are the exceptions and only time will tell if the work they produce is a symptom or a reflection of our material culture, and if it is as significant as the prices would have you believe.

Damien Hirst – Stroud, Gloucestershire

Damien Hirst’s vast studio complex in Stroud used to belong to the sculptor Lynn Chadwick. According to Hirst, when Chadwick visited the space just after it had been redesigned and expanded, his first words were, “This is not a studio, it’s a showroom.”

Hirst relates this anecdote with some pride while we are having lunch, in a kitchen next door to the vast, hangar-like room that looks more like a gallery than anything else. The walls are lined with Hirst’s work and the work of younger artists he has bought.

Until recently, Hirst employed 150 people on his studio production line, including fine artists, sculptors, fabricators and formaldehyde specialists. Now, there are around 70. “I would have let them go with or without the recession,” he says. “Art is the map of somebody’s life and, for me, the Sotheby’s auction last September was definitely a beautiful place to stop making big fuck-off work. I’m getting older. People are dying around me. You spend 20 years celebrating your immortality and then you realise that’s not what it’s about.”

To this end, Hirst has called a halt to the mass production of his signature spot paintings and his spin paintings, and to what he calls “all the big statement stuff”. Instead, he has gone back to basics and is “just painting objects”. I ask him if he is actually applying the paint to the canvas himself. “Yeah,” he says nonchalantly. “It’s all my own work. I’m still making fact paintings, copying photographs in oil and having teams of people all making the work. But I’m also painting my own paintings from start to finish.”

Hirst has smaller studios attached to his houses in Mexico and Devon. He’s also been given a room at Claridge’s Hotel. “I did some paintings for the Connaught Hotel and Paddy [McKillen, the owner of both establishments] gave me a studio in return. I paint there and nap there in the afternoons. There’s paint all over the walls, sinks, curtains. They don’t seem to mind.”

In Pop Life, the Tate will be exhibiting Hirst’s work from his 2008 Sotheby’s auction, Beautiful Inside My Head Forever. Total sales for the two-day event came to £95m and works sold included a steel cabinet of diamonds, which went for £5.2m. When I ask what he thinks of his work now, he says, “I’d say there are five great pieces: the diamond skull, the fly piece, the shark and the golden calf. I like the unicorn piece, too.”

He sits silent for a minute, staring at the bloodied remains of his steak. “I had a big dance with conceptual art,” he says, “but there are things in art that are a dead end. Conceptual art, abstraction, they’re total dead ends. You start thinking, there’s enough bloody objects in the world, why are you making more of this shit. If I’m being brutal about it, that’s what I’m thinking right now.” Suddenly, the empty studio next door makes a whole lot more sense.

Jeff Koons – Manhattan, New York

Jeff Koons employs 120 assistants in his New York studio. Photograph: Steve Pyke

In midtown Manhattan, a pristine white stone building sits amid the industrial warehouses and storerooms by the river. The first thing you see as you peer through the glass doors is a giant, glossy gorilla sculpture. This is Jeff Koons’s HQ, the centre of a global art empire. Of all the studios I visited, it seemed the closest to the Warholian model of mass production.

“It’s not a factory,” says the preternaturally calm and ever-smiling Koons. “It doesn’t emulate a factory. It’s about production, like any artist’s studio, but not on a big scale. I probably produce 10 paintings a year that go out into the world. Back in the 1980s, I’d look at the market and see Andy’s work and see that he produced so many things, and I’d look at Jasper Johns’s work and see that he produced so very little. I always kind of thought that there might be something a little more in between.”

Koons employs around 120 people, most of whom work on the making of his paintings and sculptures in several studios adjoining his office.

“It’s a hub, really,” he says. “A lot of different information comes together here from a lot of different areas. At a certain point, I realised I needed to have other people work with me because I wanted to control the production. At the end of the day, it’s exactly the same responsibility. As long as you are making the gesture that you want to make, it’s the same. Plus, sometimes, if you are involved in making a work from start to finish, sitting and painting or whatever, the material can seduce you and you can just get lost in the journey. You can set out to make a turkey and end up making a bear. When you have more distance, you can make clearer decisions.”

Koons’s work, and his reputation, remains hotly contested by critics despite – or maybe because of – the huge prices it commands at auction. Rabbit, which features in the Tate show, was valued in excess of $8m in 2008.

In 1988, one of his giant porcelain sculptures, Michael Jackson and Bubbles, sold for $5.6m. Two years ago, a giant inflatable piece, a magenta-coloured Hanging Heart, fetched nearly $34m. (Revealingly, a pink version of the same fetched $11m in a private sale recently, suggesting that the art market may finally be imploding as the global recession deepens.)

“Having value attached to it is just one way that a society can say they like the work,” says Koons, “but there is a difference between importance and significance. I mean, publicity or a presence in the media gives it a sense of importance. But significance is different, it’s more profound.”

Tracey Emin – Spitalfields, east London

Tracey Emin’s East End studio is, she tells me, built on the spot where a Roman hospital and burial ground once stood. “It has,” she says, “a good energy.”

When I visited, Emin and an assistant were busy sewing.

It seemed a calm, even cosy, space. “It’s not a sanctuary,” she says, “because my office is in here, too, and I have four assistants and the phone never stops and we have 100 emails a day to deal with. There’s always stuff happening. It never stops.”

When Emin started out as an artist in the early 1990s, after a stint at the Royal College of Art, she did not have a studio of her own and made all her work in her tiny two-room flat in Waterloo. “When I was younger,” she says, “I could never have imagined having a studio like this. Ever.”

In 1993, with fellow artist Sarah Lucas, she opened The Shop in Bethnal Green (which will be recreated for the Tate show), selling both their work, plus T-shirts, badges and ashtrays that they had made. The following year Emin had her first show at the White Cube gallery and called it My Major Retrospective, because she “honestly thought it would be the only show I ever had”. It is the remnants of both these projects that will feature in Pop Life.

“There was no irony in that early work,” she says. “We were struggling artists desperately trying to make a living. We were making things to sell to make money.”

Now, when she experiences a creative block, Emin tries to make work in the spirit of The Shop. “I just try and have some fun, shake it out, enjoy the act of being creative.”

Twice in those early days, Emin had to destroy work that she had made because, she says, she had no room to store it and couldn’t even give it away. Now, she is building an even more expansive studio in Spitalfields that will have “loads and loads of storage space, a big archive of my work and materials”.

She says that her work “changes with the space”. In her previous studio, where there were wooden floors, she made loads of blankets. In her current studio, where the floor is made of stone, she has made hardly any. Once, when she shared a studio with the painter Gary Hume, she experienced what she calls “creative osmosis”, in which “all my colours became very Garyish, and my sewing became very Hume-like.”

By the time she reaches 50, she wants her office “to be streamlined and work incredibly efficiently”, so that she does not have to concern herself too much with “all the other stuff that goes with the job”.

I ask her if her studio is a place where ideas are born. “No,” she says, without a pause for thought. “It’s a place to execute the ideas. The ideas themselves usually happen when I’m swimming in the pool or on aeroplanes, when I’m untouchable and nothing can get to me and I’m truly in a place of my own inside my head.”

Gavin Turk – Hackney, east London

Gavin Turk in front of a vast silkscreen in his east London studio. Photograph: Karen Robinson

Gavin Turk’s studio is a lock-up in Hackney, near a flyover and close to the frantic work-in-progress that is the Olympic Stadium. The first thing you see as you enter is a large Warhol-style silkscreen of Turk as Joseph Beuys. Identity, ambiguity, self-perception, these are the amorphous themes that Turk plays with constantly in his work.

“I’m very interested in cliche and the notion of what art can be, so Warhol is a constant presence. He’s there in the Pop piece, of course [Turk’s waxwork of himself as an amalgam of Sid Vicious and a gunslinging Elvis Presley] and in my silk-screened self-portraits.”

Turk jumps up and drags out a silkscreen of himself as Warhol, complete with a fright wig. “I kind of think of Warhol every time I sit at a computer. There’s an art button on every computer that allows you to Warholise even your family snapshots and portraits. That’s how omnipresent he is, even if we don’t realise it.”

Turk employs six assistants to help make his work. “It’s more about time management than anything,” he says. “They do stuff I don’t have the time to do.”

In an adjoining room that looks like a garage, he has an industrial-size paint sprayer. A long table covered in paint and paper doubles as a silkscreen bed. “We’re not that good, but that kind of works because I want to keep the image scruffy. Professional silkscreeners always do it too perfectly.”

In Pop Life, Turk will be represented by Pop and by Cave, his famous blue heritage plaque commemorating himself.

“I heard initially that the show was going to be called Sold Out, and I really like that title. At what point does bringing art into public awareness become selling out? Can you embrace the market without selling out somehow? These are old-fashioned questions now, but they still resonate.”

He tells me an illuminating story concerning one of his more provocative early works, a drawing of his signature. “I had sold it to a collector, but it was still in the studio, when a mate of mine bashed into it. I said, ‘Be careful, mate, someone’s just bought that for 600 quid.’ He looked at me as if I was mad, then he picked up the piece and stared at it really intensely for about 10 minutes. He was trying to see what 600 quid looked like. The money element had made him look closely at the work in a way he would not have done otherwise. It was all really odd. It made me realise how much money affects the way we look at art, how much it affects the way we look at the world.”

Takashi Murakami – Long Island, New York

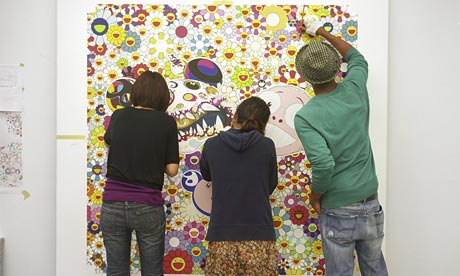

Assistants at work in Takashi Murakami’s New York Studio. Kaikai Kiki New York, LLC Artwork © Takashi Murakami/Kaikai Kiki Co Ltd Photograph: Steve Pyke

Takashi Murakami utilises the style and iconography of contemporary Japanese pop culture – cute but creepy cartoon characters, manga-style superheroes – to make high art that sells for stratospheric prices. His empire includes studios in Japan and America employing around 100 people; a biannual art fair, Geisai, in Tokyo which promotes the work of young, cutting-edge Japanese artists, and his global merchandising business, KaiKai Kiki, selling everything from videos, T-shirts and mouse pads to mobile-phone pouches and limited-edition Louis Vuitton leather bags.

In Murakami’s Long Island studio, several large, pristine rooms are devoted to the extraordinary production process that leads to one of Murakami’s “superflat” paintings. It begins when a computerised blueprint for a painting arrives from Japan. The computer data is meticulously converted to a format suitable for silkscreen printing.

“When we work on a large-scale piece, we need six full-time staff members present at all times,” says Murakami. “The job requires an incredible amount of technical skill, and even after being stuck at their desks for more than 16 hours a day, it can still take three whole weeks to complete.”

Then comes the mixing of the paint for the silk-screening process, which can sometimes utilise 1,000 screens for a single painting. “Even then,” says Murakami, “we’re not finished. After three months of painting by my assistant painters, the finishing painters will refine the results. Rather than use data or models as their guide, they have an eye for balance, and their job is to ensure the piece can stand alone as a complete work of art. This task is more similar to what you might have found at Rubens’s workshop long ago,” he says.

Only then does Murakami himself turn up to inspect the result and “decide what to leave alone and what to change”. His creative perfectionism can often lead to “drastic changes” that, he says, “earn me the ire of my staff … but ultimately add to the strength of the work”.

Murakami, for all his embracing of consumer culture, seems to lead an ascetic life, living in a spartan room in his Japanese studio. In Long Island, his huge studio space is spotless and utterly functional – a factory, maybe, but a very clean, calm one. “I’m not a perfectionist,” he claims. “In fact, I can’t do anything right. I get angry and depressed easily and I always have a hard time coming up with new ideas. The least I can do at times like this is to keep my studio clean, hoping to alleviate my creative block.”

• Pop Life: Art in a Material World is at Tate Modern from 1 October 2009 to 17 January 2010 (www.tate.org.uk)